I go to my local bookstores in search of a books written by nineteenth century women. “Are there any nineteenth century travel accounts written by women?” I ask the bookstore clerk.

I go to my local bookstores in search of a books written by nineteenth century women. “Are there any nineteenth century travel accounts written by women?” I ask the bookstore clerk.

I’ve read Dickens American Notes about his travels in North America in the early 1800s, as well as James Fenimore Cooper’s accounts of travels along the Rhine. Friedrich Engels, of Marx-Engels fame, wrote an account called The Campaign for the German Imperial Constitution, which includes his experiences in the Palatinate in 1849. But I’m hoping to broaden the perspective, to catch a glimpse of a woman’s point of view.

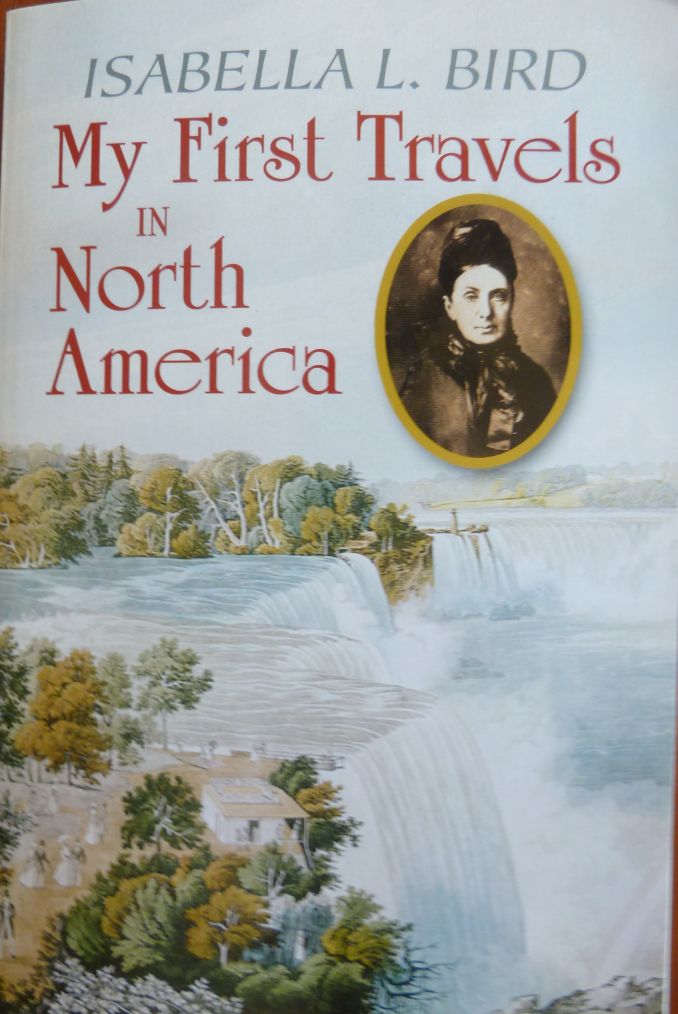

By the time I leave the bookstore, I have Isabella Bird’s My First Travels in North America in hand, and Katherine Frank’s A Voyager Out on order. I’ve blogged about Bird’s book here. Since, then, I’ve heard from a woman journalist in the UK who is currently traveling through China in Isabella Bird’s footsteps. She’s been at it for ten months now, and just resumed her journey after a brief hiatus. You can follow her travels at Time To Fly Free.

Much later, I get around to reading Katherine Frank’s A Voyager Out. A biographical account of the life of Mary Kingsley, the first four chapters are an obligatory background family tree (so-and-so begat so-and-so). I have trouble sticking with it, but the bookstore clerk told me it was her favorite book of all time, so I hang in there.

At Ch. Five, we finally get to Kingsley’s voyages, and the amazement, wonder, and chutzpah that make this book so memorable. Mary Kingsley departs from England to Africa saying she is going to study African ethnography. She is well aware of the risks, in an abstract way as she sets out on a cargo ship, and in a very real way once she arrives in West Africa. In the Victorian era, it seems, a significant number of Englishmen died of disease, dysentery, and madness in Africa. Numerous deaths are chronicled in A Voyager Out as Kingsley passes from Sierra Leone to the Gold Coast to Cameroon and as far south as the French Congo.

Although chronically ill at home in England, on her journeys, Kingsley appears immune. In England, she suffers from all sorts of illnesses: “influenza, neuralgia, migraines, heart palpitations, even rheumatism.” In fact, originally Kingsley imagines her travels in West Africa will result in her tragic end. Since “no one had need of me anymore when my Mother and Father died within six weeks of each other in 1892 and my brother went off to the east, I went down to West Africa to die.” Improbably by all accounts, she survives and thrives.

Mary Kingsley negotiates her way through the remotest of African villages as a trader. Perpetually dressed in high-collar Victorian clothes, she sleeps in village huts and eats local food, hacks her way though the jungle with a machete, navigates rivers in her own canoe, and nurses all manner of sick and dying people along the way, all in order to study African customs and beliefs. Her book Travels in West Africa endures as a landmark work to this day.