I left Buffalo heading south to the upper Ohio River valley to fit in a little book research on the Scots Settlement. On the way, I decided to make an extracurricular stop at the Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz Museum in Jamestown, NY, just to see what it was like.

I left Buffalo heading south to the upper Ohio River valley to fit in a little book research on the Scots Settlement. On the way, I decided to make an extracurricular stop at the Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz Museum in Jamestown, NY, just to see what it was like.

Often it’s these off-the-beaten-track side trips that bring about the most wonderful encounters, and this sojourn proved no exception. I had just seen a sign that I’d entered Conewango, NY, when a horse and wagon trotted over the rise in the road coming straight toward me, then made a sharp turn into … a blacksmith shop! By the time I’d figured out I wasn’t imagining things, I was a quarter mile down the road.

Often it’s these off-the-beaten-track side trips that bring about the most wonderful encounters, and this sojourn proved no exception. I had just seen a sign that I’d entered Conewango, NY, when a horse and wagon trotted over the rise in the road coming straight toward me, then made a sharp turn into … a blacksmith shop! By the time I’d figured out I wasn’t imagining things, I was a quarter mile down the road.

Of course, I turned around. Sure enough, the sign for the shop hung plain as day: Rabers Blacksmith Shop. The horse and wagon I’d seen was parked right out front. I pulled into the parking lot and hopped out of my car, camera in hand. I wasn’t going to miss the opportunity to witness a working blacksmith shop in the 21st century. No sirree bob.

Of course, I turned around. Sure enough, the sign for the shop hung plain as day: Rabers Blacksmith Shop. The horse and wagon I’d seen was parked right out front. I pulled into the parking lot and hopped out of my car, camera in hand. I wasn’t going to miss the opportunity to witness a working blacksmith shop in the 21st century. No sirree bob.

Just then, a young man with a black beard, broad-brimmed Amish-style hat and a kind smile strode by. He glanced down at my iPad.

Just then, a young man with a black beard, broad-brimmed Amish-style hat and a kind smile strode by. He glanced down at my iPad.

“Mind if I take some pictures?” I asked.

He gazed at me reasonably. “That’s fine. Just don’t include any people in the shots.”

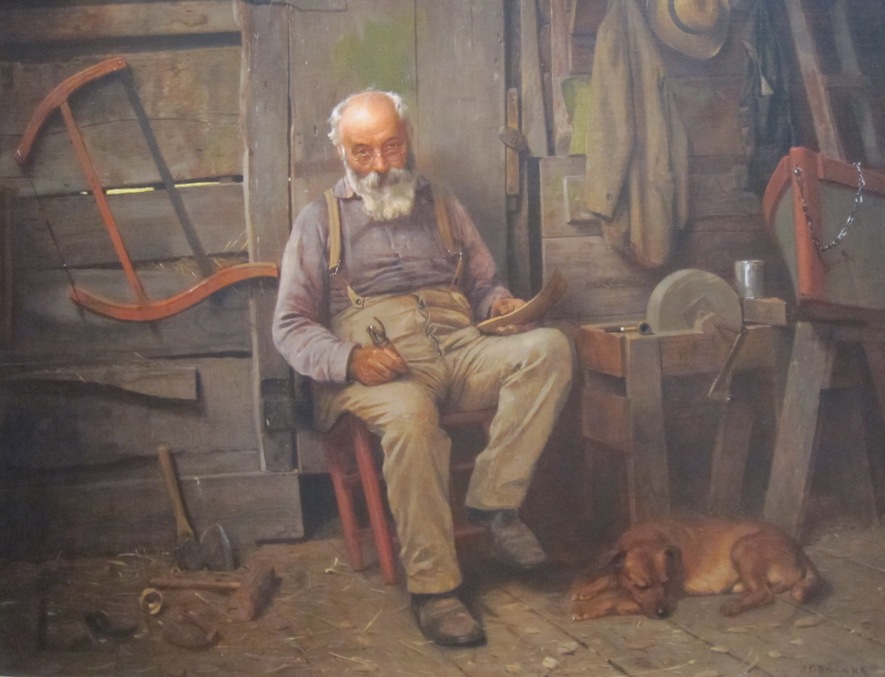

As we walked toward the shop, I nearly cackled with happiness but managed not to, thank God. Inside, the forge fires weren’t lit just then, but I soaked in the ramshackle array of metal and rust, tools and worn wood. One blacksmith was just then loading a box of horseshoes. I asked if that was the bulk of their work.

As we walked toward the shop, I nearly cackled with happiness but managed not to, thank God. Inside, the forge fires weren’t lit just then, but I soaked in the ramshackle array of metal and rust, tools and worn wood. One blacksmith was just then loading a box of horseshoes. I asked if that was the bulk of their work.

“We used to do wrought iron work, but we got out of that,” he said.

“I hear wrought iron is a little hard to come by these days,” I said.

“Yup.”

I lingered for a while, talking with three blacksmiths in all about the changes in the artisan craft, about how I’d written a novel, oddly enough, about 19th century blacksmiths, and about how guys who were practically kids showed up at the Raber shop these days to watch and ask questions, which we all saw as a positive trend. It pleased me to leave a book with them, in trade for taking the photos. As I handed it over, the white pages were instantly blackened by coal-dusted hands. The blacksmith laughed. “A book’s gonna get dirt on it pretty quick in a blacksmith shop,” he said.

I lingered for a while, talking with three blacksmiths in all about the changes in the artisan craft, about how I’d written a novel, oddly enough, about 19th century blacksmiths, and about how guys who were practically kids showed up at the Raber shop these days to watch and ask questions, which we all saw as a positive trend. It pleased me to leave a book with them, in trade for taking the photos. As I handed it over, the white pages were instantly blackened by coal-dusted hands. The blacksmith laughed. “A book’s gonna get dirt on it pretty quick in a blacksmith shop,” he said.

I smiled appreciatively, not minding in the slightest. Back on the road, I continued toward Jamestown, thanking my lucky stars.