As I talk with friends and writers about research progress for my current novel about Scottish immigrants to America in the 18th century, their eyes light up. “So what are you finding out?” they want to know.

I flounder for an answer to this question, because very little is straightforward. I’ll stumble upon a thread of historical interest here, another there. In isolation, the info doesn’t mean all that much. Woven together, though, a tapestry begins to emerge.

For instance, a book I came across at Fairview Park Library in Cleveland. When I arrived, I went first to the reference desk.

For instance, a book I came across at Fairview Park Library in Cleveland. When I arrived, I went first to the reference desk.

“I’m looking for information about Scottish immigrants,” I said.

“You’re talking to one,” said the librarian. Her accent wasn’t overt, but she still had a trace of that charming Scottish burr. “What do you want to know?”

Delighted, I introduced myself and we chatted over topics such as the Orange Walk, Hogmanay and cultural differences between Edinburgh and Glasgow.

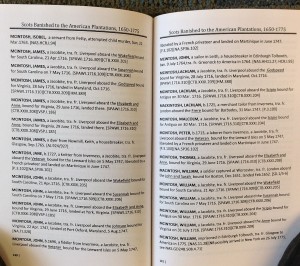

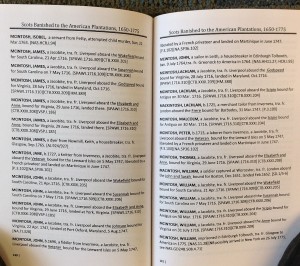

Until her phone rang, that is, at which point I moved on to browse the genealogy stacks, where one title in particular grabbed my interest: Scots Banished to the American Plantations, 1650-1775.

Banished. Even in genealogy circles, that word doesn’t crop up every day. I wondered how many McIntoshes, Smiths and Stewarts had been banished. Any of them from my region of Inverness-shire? As it turned out, quite a few. Regarding McIntoshes, a Jane, John, and Peter–a knitter, fiddler, and laborer–had all been transported/banished by the Brits from Inverness to the “Leeward Isles” in 1747. (But a French privateer intercepted the ship and took them to Martinique instead.)

1747. Just one year after the 1746 failed Jacobite rebellion that occurred at the Battle of Culloden, on McIntosh clan land, in Inverness. What struck me too was the number of banishments listed in the 1600s and early 1700s, and well beyond 1746 into the 19th century. Pages and pages of names. Each of these persons–whether soldier, merchant tailor or housebreaker–was sent, nay banished, to the Americas against his or her will.

Then this morning as I browsed through a book about John Knox and the Scottish Reformation (a movement that began in the 1500s), a similar thread emerged. After the aborted revolt in Scotland of Prince Charles Stuart in 1746, the book notes, “the English instituted a policy of stern repression in Scotland, and many of the adult men left that country.” (p.212-213, Douglas Wilson, For Kirk and Covenant)

Hmm — “many of the adult men left.” A tad misleading, yes? It seems to me many, if not most, of both men and women were banished against their will. Expediently shipped to a place of no return, torn from their families and a land they dearly loved.

Hence, I’m finding out the Scots endured a radically different experience than the Puritans, Quakers, Protestants, Jews and so on, those early settlers who made their exodus to the American colonies due to religious persecution, yes, but in solidarity, and mainly in search of liberty. The Scots, on the other hand, were transported, suffering isolation from their clans and disaffection from their captors and British colonial authorities. When these Scots arrived in the land of liberty, they came to serve a jail sentence. Perhaps a miscalculation on the part of the British crown? Scots rapidly grew in number to become a hefty chunk of the population.

a body of about 600,000 Scots made up about one-fourth of the population [of the American colonies] at the time of the Revolution. [p. 19, Morton Smith’s Studies in Southern Presbyterian Theology]

And, as brave warriors, they fought valiantly in the American Revolution. In his book For Kirk and Covenant, Wilson posits that these same Scots brought with them a stubborn conviction in representative government, the rule of law, and separation of church and state. Could one go so far as to claim the U.S. government was founded by Scots Presbyterians? Well, they ought at least to be in the running, along with the Transcendentalists, the Freemasons, the Illuminati …

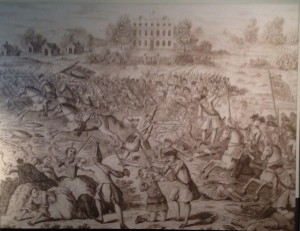

We’ve made it up to Inverness, where our first stop yesterday was the Culloden Battlefield Visitor Centre. In April of 1746, a loose coalition of Highland clans mustered to the call to restore the Catholic Stuart dynasty to the Protestant Hanoverian English throne. The ill-fated political and military manuevres of Prince Charles Edward Stuart failed at this very place called Culloden. Not always a student of history, I had no idea how large this event loomed in Highland memory.

We’ve made it up to Inverness, where our first stop yesterday was the Culloden Battlefield Visitor Centre. In April of 1746, a loose coalition of Highland clans mustered to the call to restore the Catholic Stuart dynasty to the Protestant Hanoverian English throne. The ill-fated political and military manuevres of Prince Charles Edward Stuart failed at this very place called Culloden. Not always a student of history, I had no idea how large this event loomed in Highland memory. Until recently, I mainly knew about this battle from family lore, which goes that my ancestor Daniel Mackintosh was a newborn infant in a croft (a thatched peasant hut) on that very Culloden field where the battle flared up that day. When it was clear the Highlanders were in retreat, his mother (my 4x great grandmother) was forced to gather up her babe and run for it.

Until recently, I mainly knew about this battle from family lore, which goes that my ancestor Daniel Mackintosh was a newborn infant in a croft (a thatched peasant hut) on that very Culloden field where the battle flared up that day. When it was clear the Highlanders were in retreat, his mother (my 4x great grandmother) was forced to gather up her babe and run for it. Now Culloden is an uninhabited field, but this artwork of the battle depicts a manor and homes on the grounds. (Double-click on the image for a large view). It was a chilling day for the 13,000 Highland and British men who engaged in the rout, which ruined Jacobite hopes and started the final demise of the Gaelic Highland clans.

Now Culloden is an uninhabited field, but this artwork of the battle depicts a manor and homes on the grounds. (Double-click on the image for a large view). It was a chilling day for the 13,000 Highland and British men who engaged in the rout, which ruined Jacobite hopes and started the final demise of the Gaelic Highland clans. It was a productive visit, especially since this Scotsman helped me arm for battle as a Highlander. I tried on a shield and sharp dirk (dagger) with my left arm and hand, and clumsily practiced wielding a heavy, basket-hilted sword with my right. The Scotsman only flinched once.

It was a productive visit, especially since this Scotsman helped me arm for battle as a Highlander. I tried on a shield and sharp dirk (dagger) with my left arm and hand, and clumsily practiced wielding a heavy, basket-hilted sword with my right. The Scotsman only flinched once.