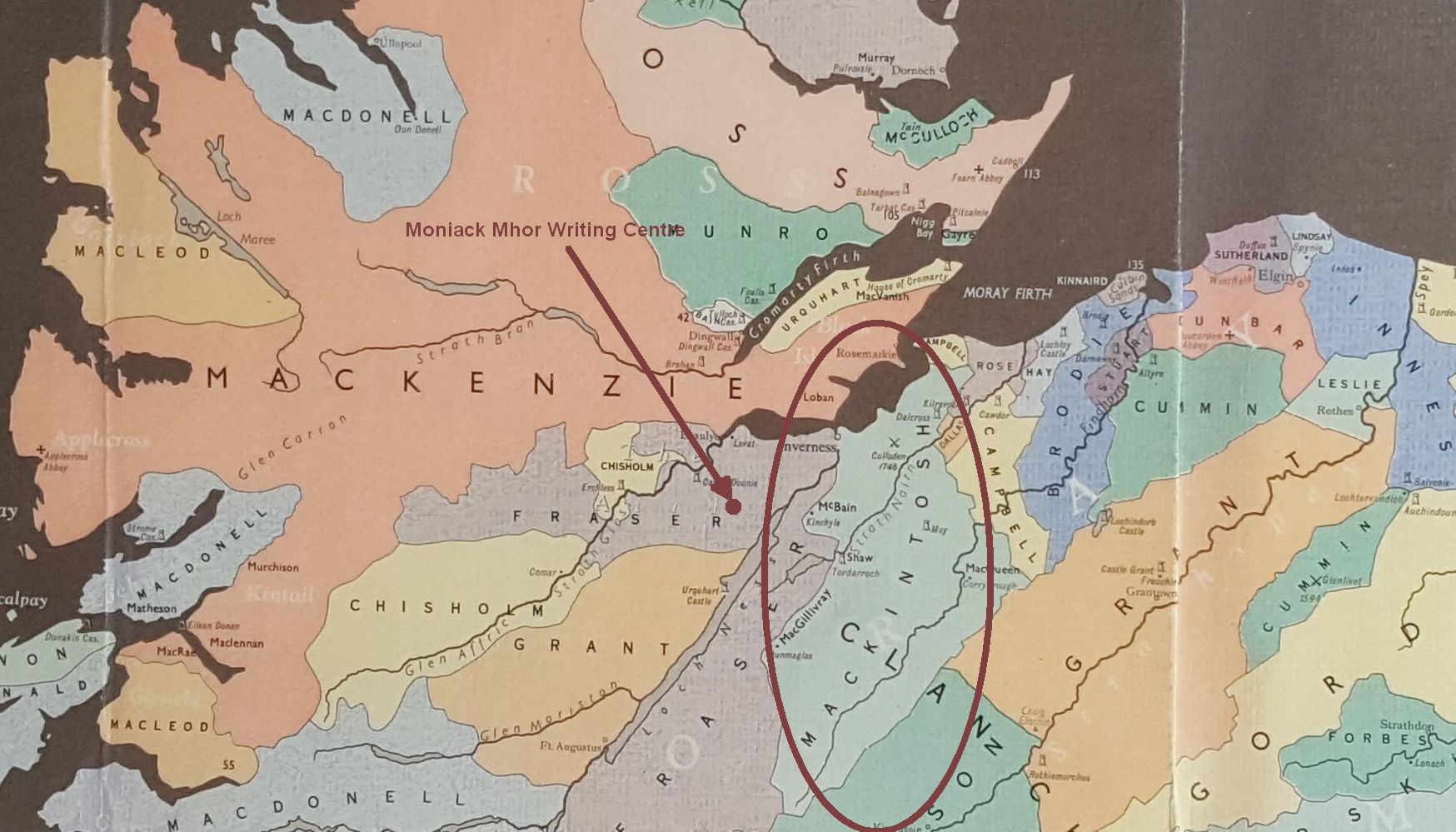

Since Moniack Mhor, I’ve been traveling willy-nilly from Inverness to Stirling to Glasgow to Forres. One reason being, I have a Spirit of Scotland Travelpass, which means I can take the train anywhere I want for 8 days out of the next 15. So, why not?

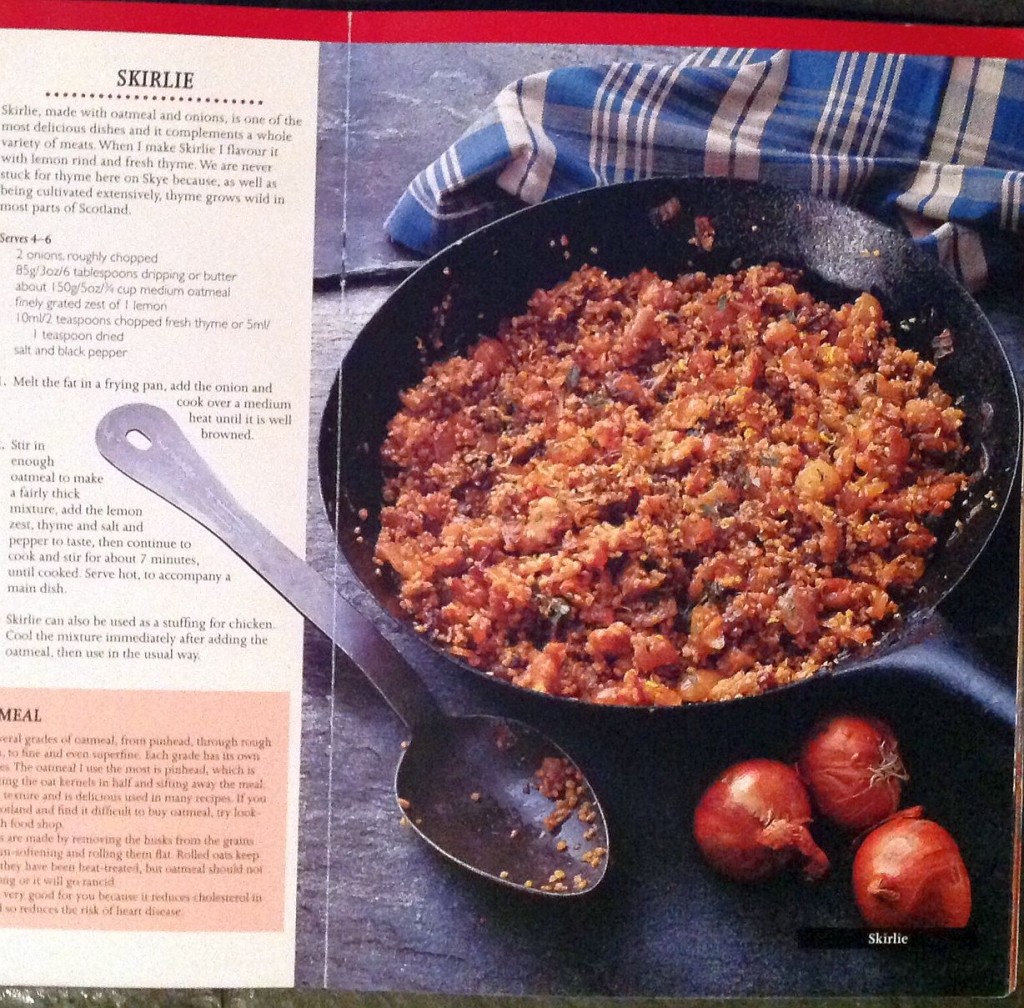

First, I hied it down to Stirling to see friends, who introduced me to all kinds of Scottish treats, including the Wallace Monument (Wally Monnie) and duck pie.

The top of Abbey Craig, where the Wallace Monument stands, offers a terrific view of the Ochil Hills and Ben Lomond.

Plus, my host Ken took me down a “secret path” to a dizzying cliff where he used to rock-climb, that is until someone pulled loose rocks that fell on passing cars on the road down below, which put an end to that climbing wall.

Next I zoomed south to Glasgow for a quick stop-in at University of Glasgow and the Hunterian galleries. A feature at The Hunterian was this Harry Potter-style chair called The Blackstone, an ornately carved wooden chair with a stone inlaid in the seat. The placard explains: “From the foundation of the University of Glasgow in 1451 until the middle of the 19th century all students were examined orally, seated on the Black Stone. This slab of dolerite is now embedded in an oak chair made in 1775-6. At the top is a time-glass surrounded by bay leaves. As the examination began, the Bedellus bearing the mace set the time-glass and after about 20 minutes, when all the sand had flowed through, grounded the mace with the word Fluxit (“it has flowed through”). He then turned to the senior examiner with the words “Ad alium, Domine (“On to the next one, Sir”).

Next I zoomed south to Glasgow for a quick stop-in at University of Glasgow and the Hunterian galleries. A feature at The Hunterian was this Harry Potter-style chair called The Blackstone, an ornately carved wooden chair with a stone inlaid in the seat. The placard explains: “From the foundation of the University of Glasgow in 1451 until the middle of the 19th century all students were examined orally, seated on the Black Stone. This slab of dolerite is now embedded in an oak chair made in 1775-6. At the top is a time-glass surrounded by bay leaves. As the examination began, the Bedellus bearing the mace set the time-glass and after about 20 minutes, when all the sand had flowed through, grounded the mace with the word Fluxit (“it has flowed through”). He then turned to the senior examiner with the words “Ad alium, Domine (“On to the next one, Sir”).

After a mere couple of hours in Glasgow, Scotrail whisked me back north to Forres, the former seat of MacBeth.