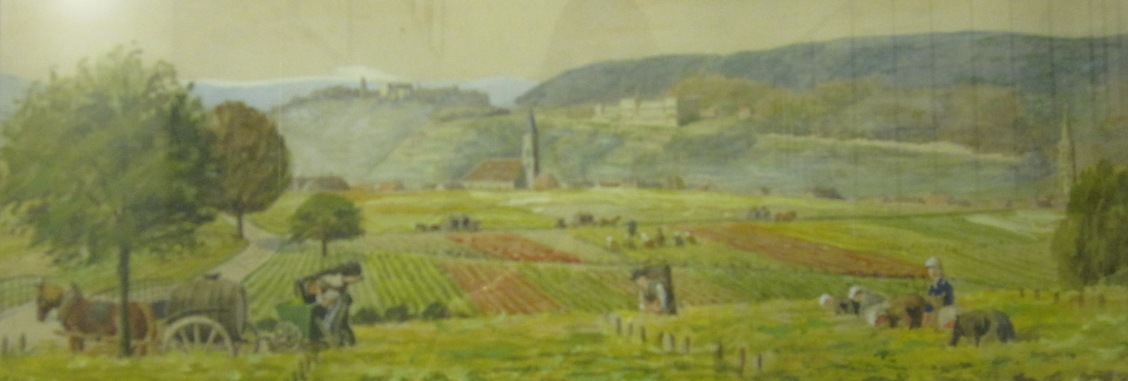

My last weekend here I participate in the City of Freinsheim’s “Weinlese” (grape harvest). We dress against the damp and cold, and warm up with sips of Stadtwein as soon as we arrive.

My last weekend here I participate in the City of Freinsheim’s “Weinlese” (grape harvest). We dress against the damp and cold, and warm up with sips of Stadtwein as soon as we arrive.

The Mayor of Freinsheim, town council members, the head of the Verbandsgemeinde (the political administration of eight small villages) and two of the region’s wine princesses have all gathered to pitch in.

The Mayor of Freinsheim, town council members, the head of the Verbandsgemeinde (the political administration of eight small villages) and two of the region’s wine princesses have all gathered to pitch in.

Local wine-makers have also come to help, haul away the harvested grapes, and transform them into Stadtwein. The city gives bottles of wine to the elderly in the village on milestone birthdays (70th, 80th, and so on).

Local wine-makers have also come to help, haul away the harvested grapes, and transform them into Stadtwein. The city gives bottles of wine to the elderly in the village on milestone birthdays (70th, 80th, and so on).

After a session of pass-the-glass, we set to work on three rows at the edge of town. I’m told it is the worst harvest in 25 years due to so much rain. The vines are producing 60 percent less than normal.

After a session of pass-the-glass, we set to work on three rows at the edge of town. I’m told it is the worst harvest in 25 years due to so much rain. The vines are producing 60 percent less than normal.

Manfred shrugs at the news. “What can you do? This is wine-making.”

Manfred shrugs at the news. “What can you do? This is wine-making.”

The job would normally take 3-4 hours, but with so  few grapes, we’re done in 45 minutes. Afterwards, we gather at the Von Busch-hof Restaurant for speech-making, beef stew and kuchen.

few grapes, we’re done in 45 minutes. Afterwards, we gather at the Von Busch-hof Restaurant for speech-making, beef stew and kuchen.

Tomorrow, I’m homeward bound. Auf Wiedersehen.